-40%

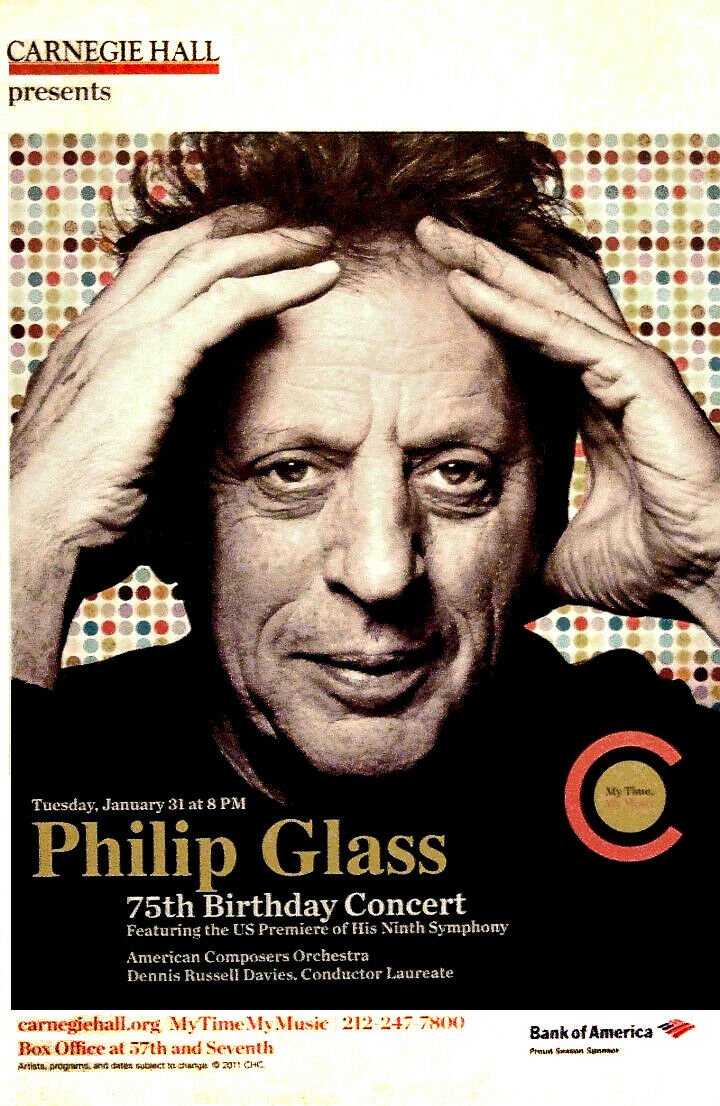

1959 Violin CONCERT POSTER Israel MICHAEL RABIN Beethoven HINDEMITH Brahms

$ 66

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

Up for auction is an original CONCERT PROGRAM of the renowned deceased JEWISH Violinist , The child prodigy MICHAEL RABIN . The VIOLIN CONCERT took place in 1959 in ISRAEL.

Young RABIN was then only 23 years of age. RABIN played pieces by HINDEMITH , BRAHMS and BEETHOVEN .

The IPO was playing under the baton of the Israeli conductor MICHAEL TAUBE . ENGLISH and HEBREW.

Size a

round 27 x 19 " . Hebrew & English. Very good condition . ( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) Will be sent inside a protective rigid sealed tube .

PAYMENTS

: Payment method accepted : Paypal .

SHIPPMENT

:SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25 . Will be sent inside a protective packaging

.

Handling around 5 days after payment.

Michael Rabin (May 2, 1936 – January 19, 1972) was an American violinist. He was one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century.[1] His fame has continued despite his untimely death at the age of 35. Michael Rabin was of Romanian-Jewish descent. His mother Jeanne was a Juilliard-trained pianist, and his father George was a violinist in the New York Philharmonic. He began to study the violin at the age of seven. His parents encouraged his musical development. After a lesson with Jascha Heifetz, the master advised him to study with Ivan Galamian, who said he had "no weaknesses, never." He began studies with Galamian in New York and at the Meadowmount School of Music and the Juilliard School. His Carnegie Hall debut took place in January 1950, at the age of 13, as soloist with the National Orchestral Association, playing the Vieuxtemps Concerto No. 5[2] under the direction of Léon Barzin. Subsequently, he appeared with a number of American orchestras before his Carnegie Hall debut on 29 November 1951, at the age of 15, in the Paganini D major Concerto, with Dimitri Mitropoulos conducting the New York Philharmonic. His first London appearance took place on 13 December 1954, at age 18, playing the Tchaikovsky Concerto in D at the Royal Albert Hall with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Michael Rabin recorded concertos by Mendelssohn, Glazunov, Paganini (No. 1 in D major; 2 recordings), Wieniawski (No. 1 in F-sharp minor, No. 2 in D minor), and Tchaikovsky, as well as Bruch's Scottish Fantasy and the Paganini Caprices for solo violin. He recorded the Bach Sonata in C major for solo violin and the Third and Fourth sonatas for solo violin by Eugène Ysaÿe, as well as other virtuoso pieces, including an album with the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. Rabin played in a bel canto style. For many years, he played the "Kubelik" Guarnerius del Gesu of 1735. He toured widely, playing in all major cities in the U.S., Europe, South America and Australia. He even appeared on a 1951 episode of the variety television series "Texaco Star Theatre." During a recital in Carnegie Hall, he suddenly lost his balance and fell forward. This was an early sign of a neurological condition which was to affect his career adversely. He died prematurely at the age of 35 from a head injury sustained in a fall at his New York apartment. ****** Michael Rabin managed to be one of the most talented and tragic violin virtuosi of his generation. Hailed as a child prodigy, his talent matured gracefully into an adult level, but he failed to follow in his emotional growth, resulting in a cutting short of his career. He never reached the age of 36, yet remains one of the most fondly remembered of virtuoso violinists for listeners and fellow musicians such as Pinchas Zukerman, with whom he shared a teacher. Rabin's father was a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, and his mother a Juilliard-trained pianist. When he was a year old, Rabin was able to beat perfect time, and at three he demonstrated his possession of perfect pitch; by five he was studying the piano, and not long after, while visiting a doctor whose hobby was the violin, Rabin took up a miniature version of the instrument that was in the office and began tuning and playing it, refusing to return it. His father began teaching him the instrument soon after, but before their fifth lesson, the elder Rabin realized that his son's musicianship exceeded his own. Ultimately Rabin studied with Ivan Galamian, the future teacher of Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zukerman. Rabin made his first professional appearance in 1947, at age ten, with the Havana Philharmonic under Artur Rodzinski, performing the Wieniawski Concerto No. 1. He made his recording debut two years later, on the Columbia Masterworks label, with a set of 11 of Paganini's Caprices for solo violin. The following year came Rabin's Carnegie Hall debut, at age 13, with the Vieuxtemps Concerto No. 5, in a performance that had him hailed in The New York Times as "already an accomplished artist...play[ing] with real grace and beauty of tone." No less a figure than the conductor George Szell declared Rabin the greatest violin talent that had come to his attention in the previous 30 years, and Dimitri Mitropoulos called Rabin "the genius violinist of tomorrow." In the 1950s, Rabin signed with Capitol-EMI, for which he recorded the most important part of his legacy, including the Paganini Violin Concerto No. 1, the first and second violin concertos of Wieniawski, and the Tchaikovsky, Mendelssohn, and Glazunov concertos. At the end of the 1950s, Rabin suddenly cut short his recording career, for reasons that were never clear. He continued to perform regularly in concerts around the world, and even made broadcast recitals during the 1960s revealed his talents undiminished. There were accounts of his emotional instability, and an unstable personal life -- he had a rough time adjusting to the change from child prodigy to adult virtuoso, though his talent showed no signs of abatement; during the late '60s there were stories of chronic drug use; he also displayed some unusual neuroses, including a fear of falling off the stage, but none of that should have affected his recording career while leaving his concert career intact. In any case, Rabin never entered a recording studio again after 1959, and in 1972, while still in the prime of his life died in a fall when he slipped on a parquet floor and struck his head on a chair. Rabin's legacy on record is principally concentrated in EMI's catalog. The complete Paganini 24 Caprices for solo violin are available as a single CD, while the rest of his output has been released in a six-CD set, containing virtually all of his concerto recordings. They remain seminal recordings of each of the pieces. ~ Bruce Eder, Rovi ****** Thoughts on Rabin's Caprices I first heard about Michael Rabin while discussing favorite performances of the Paganini Caprices. We all know preference is subjective; always up for argument. His Caprices were referred to as such often enough, however, as to warrant notice. I've always loved Ilya Kaler's caprices. Their flowing, reverberating sound makes for easy listening. His phrasing and most things about the performance hold about as much draw for the untrained ear as the caprices can. The tone is wide and glowing and colorful. Much of this is certainly due to recording techniques and contemporary technology. It sounds like it was recorded in a large hall with the mic a distance from Kaler. Rabin's recording of these works available on this site surprised me at first. The hall-like sounds and reverb that are present to some extent in many other recordings of the caprices were not there. It sounds like the mic was fairly close to the violin. Every extraneous thing is stripped away. What you're left with is a sound like Rabin is in a small room with you, playing six or eight feet away from you. This, given a violinist of Rabin's natural skill and temperament, is rivetingly exciting! Audible are tiny details of his playing. More than highlighting errors, however, the scrutiny this recording allows only exposes deeper glory with regard to his tone, intonation, musicality and the ease with which he played. The recording is a clear and amazing testament to Rabin's skill. Typical of Rabin, his momentum never concedes to challenge; tempo slows and quickens but never for a technical reason. I found the tone in general to be amazing, especially the clarity and precision in his high double stops. As usual plays hard and has fat, rich tone which absolutely sings in longer notes. One interesting note is that despite the fame of the 24th Caprice, I often find other artists' interpretations and playing of the 24th to be below average compared to their other caprices. With Rabin, however, I would encourage you to listen to the 24th first, not because the familiarity of this popular piece makes it an easy benchmark to judge by, but because this diverse caprice is a broad field for Rabin to show his skills. These are some of the most obvious reasons to appreciate Rabin's complete recording of these pieces that Paganini originally wrote as etudes. -Trevor Ford ***** In the history of the violin, this is the Age of Perlman. He is the most recognized violinist since Heifetz and the greatest of the Galamian pupils. In fact, the future of the violin seems firmly in the grasp of Juilliard – a host of Dorothy DeLay students are poised to succeed Perlman with their own violinistic oligarchy. None seems to stand out, however. There is too much competition for a single person to ascend the throne; the proliferation of recordings and the cultural diminution of classical music assure that individual magnetism will never again hold sway. The recordings (c. 1954 1960) of Michael Rabin transport us to the age of the violin superheros – those days when a program at symphony hall could attract a crowd of devotees. Heifetz was still the acknowledged king, the model of perfection despite his chilly demeanor. Milstein, Stern, and Oistrahk were at their shining best. And consumers bought recordings because they carried the artist's imprimatur, not the SPARS code DDD. In Samuel Appelbaum's book The Way They Play (Paganiniana Publications, Inc. 1975), there is a photo of Michael Rabin in his bathrobe. He stands before a folding, chrome music stand, holding his Guarnerius del Gesu in his left hand and a mug of coffee in his right. Rabin's head is inclined towards the music – his warm-up exercises apparently. In the left of the photo, the hallway that adjoins the practice room extends into the distance. where a female figure, in similar dishabille, retreats into shadow. On other pages we have pictures of the violinist with his prized model collection and looking under the hood of his car (he was an avid mechanic). For a book that focuses on "the way they play," it is strange to see Rabin in every guise except that of a violinist. When that interview was conducted, Rabin's concert career was over and the rest of his life was unraveling. The commitments that ensued with his prodigal launch as a teenage virtuoso had been too much for him to handle; he turned to drugs to cope with the anxieties. The coroner found barbiturates in Rabin's blood after the violinist was found dead in his apartment. He had slipped on a rug and struck his head on a table. I first heard Michael Rabin in his recording of the Paganini Caprices. A college friend had introduced me to the artistry of Itzhak Perlman, and I was interested in pursuing this music of transcendental technique. In the music library there was a two-record set of the Caprices played by this Rabin chap. The cover showed a young man, already balding, glowering down his instrument as if he had been interrupted. When I put on the old LP and Rabin lit into the first caprice, I felt an influx of adrenaline. The playing had overwhelming verve. His tone, while not as buttery as Perlman's, was fiercely dramatic. The close-up recording made him sound even over-emphatic. I will never forget the final trill of 24th caprice, a superb flourish to cap one of the best virtuoso recordings of all time. Thereafter, I paid a visits to the record archives, the Tower Records cut-out bins – anywhere I thought I might make contact with his spirit. Named by famed Juilliard pedagogue Ivan Galamian as his most talented student ever, Rabin set out to play this violin like Heifetz – every performance a hurricane of effortless technique and burnished tone. For a while, the daunting standard seemed achievable. At age ten he essayed the fearsome Wieniawski First Concerto; a few years later his Carnegie Hall debut featured the Vieuxtemps Concerto #5 in A minor, a Heifetz specialty. World-wide tours followed. The teenage Rabin recorded the violin part for the soundtrack of Rhapsody, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Vittorio Gassman in a forgettable musical intrigue. He also made his first Paganini recording, a selection of Caprices. From there the invitations to record burgeoned. Virtuoso music was the focus: the two Wieniawski concertos, the Scottish Fantasy of Bruch, and the Glazounov concerto. And of course, there was Paganini. Rabin twice recorded the First Concerto. That version, in mono, is more faithful to the concerto as an organic whole; he and conductor Galliera keep the phrasing witty and lithe. The second, recorded shortly after his twenty-fourth birthday, shows Rabin in a more assertive pose: his tone, now in stereo, simply blazes. The original Capitol LP coupled the Paganini with Wieniawski's 2nd Concerto, and as long as I have listened, neither of these recordings has been surpassed. Blessed with a fabulous natural technique and a melancholic temperament, Rabin's art is essentially at odds with itself. His conquests of showy concertos and encore pieces, with their "play to the crowd" demands, sometimes lack character. The "Zapateado" sounds a bit steely next to Perlman's suave take. In the Mendelssohn, Rabin also seems ill at ease: tempos too drawn out, his tone almost monochromatic in its relentless intensity. Surprisingly, some of the more delicate duos for piano and violin come off extremely well. "Sea-Shell" by Carl Engel showcases Rabin's amazing trill, fluttering from register to register with perfect control. He is also capable of great repose in Thais "Meditation." The Kreisler pieces have a ravishing sound, but border on schlock (Wilhelmji's transcription of the Chopin Nocturne is cloying in the extreme). The music for solo violin benefits from Rabin's concentrated approach: His Ysaÿe, if not the last word in interpretive imagination, is nicely judged. Rabin surmounts the technical hurdles without making light of them. Despite his childhood avowal to play just like Heifetz, Rabin never embarks on a performance as a stunt. His phrasing, his effulgent tone, and his flair for the dramatic save him from empty virtuosity. On the balance, this EMI set is extraordinary. The concerti are studded with moments that would be the centerpiece of many a career. For some, though, enthusiasm will be tempered by the in-your-face sonics. EMI was late getting to stereo, and their master tapes aren't in the best of shape. You can obtain a separate disc of the Caprices (now available in stereo again!). If you can't find the whole set, the least you can do is to spring for the Caprices, an enduring testament to a marvelous talent. Copyright © 1997, Robert J. Sullivan ebay5298